Walter Bush is notable for his significant early 20th century contribution to the development of Auckland, New Zealand’s largest city. In 1906 he was appointed Auckland’s City Engineer and retained this position until 1929, when he became Brisbane’s Chief Water Supply and Sewage Engineer.

Walter Ernst Bush (1875-1950), Past Presidents Album, 1914-1966, IPENZ.

During Bush’s period in New Zealand he was responsible for many notable achievements, including Auckland’s first water supply from the Waitakere Ranges, and the Okahu Bay drainage scheme – vital parts of Auckland’s infrastructure that are still serving the city over a century later.

Walter Bush was born at Kingston, Surrey, England on 8 September 1875. He became an engineering cadet at age 16, and, even then, showed a particular interest in water supply and sewerage systems. Prior to immigrating to Auckland, Bush was the Borough and Waterworks Engineer at Sudbury, Suffolk.

Auckland’s City Engineer

On 16 March 1906 the New Zealand Herald reported that Bush had been chosen from the other 120 applicants to be Auckland’s City Engineer. His credentials included being an Associate Member of the Institutions of Civil Engineers, and the Municipal and Country Engineers, as well as a Member of the Royal Sanitary Institute. Bush had also been awarded the First Premium for his thesis, ‘The Manufacture and Testing of Portland Cement,’ at the 1901 Building and Trades Exhibition in London. Auckland’s Mayor commented that “Mr Bush was a man of eminent capacity, still young, in the vigour of life with a large experience”.

Within months of arriving in New Zealand to take up his new role, Bush led a project which would help him become intimately familiar with the workings of his new home. Richard Liron Mestayer (1854–1921) and G Midgely Taylor’s Scheme of Main Drainage report to the Council recommended creating a comprehensive city plan at a scale of 40 feet to 1 inch. Bush reported the validity of this idea, and that a plan would be created, “on which shall be shown not only all the lines and boundaries of street, but also the position of all buildings, boundary fences, etc as far as can be ascertained, the exact positions of all existing sewers, gas and water mains.”

A team of up to 35 staff, including surveyors and draughtsmen, undertook the task. The result comprised 67 sheets of plans and was completed by June 1909. These highly detailed maps are among the most frequently used items at the Auckland Council Archives.

Drainage and sewerage solutions

In 1907 another of Bush’s early tasks was reviewing a variety of proposed schemes to overcome Auckland’s drainage and sewage problems, a result of 30 years of Council procrastination. Public pressure was mounting over untreated sewage discharging into the harbour at many outfalls of gully and foreshore pipelines. Bush recommended “the adoption of a comprehensive scheme to embrace not only the City, but also those suburban districts whose natural drainage was towards the Waitemata Harbour between Okahu Point and Motions Creek”.

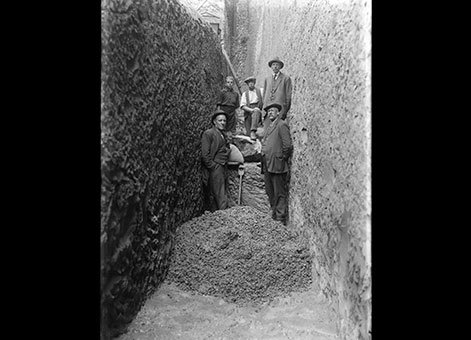

At Okahu Point screening and sewage holding tanks (now part of Kelly Tartlon’s Underwater World) were built to make sure sewage was only discharged on the outgoing tide. The resulting main sewer, oval in shape, up to 2.6 metres in depth, and at a gradient of 1 in 3,000 over 13.27 kilometres, required much tunnelling and aqueduct construction.

After much controversy, sewage was diverted from Okahu Point to the Mangere Wastewater Treatment Plant in 1960. The Auckland and Suburban Drainage Board formed in 1908 to allow the 15 suburban districts surrounding Auckland City to join in the drainage scheme. Following its completion Bush became the Drainage Engineer, a position he held until 1915 in addition to being the City Engineer.

Tackling the water supply issue

Auckland’s water supplies were in a critical state when Bush arrived in 1906. Therefore, he was immediately tasked with surveying proposed Nihotupu Valley sites for water storage dams in the Waitakere Ranges.

At this time the Waitakere Dam was being built, but the contractors were not progressing well. A major slip also hampered construction, destroying a temporary wooden dam whose freed water then washed away much of the Waitakere Dam’s construction materials.

Concurrently, there were problems with Ponsonby’s Hopetoun Street Reservoir, one of the original 1870s sloping-sided reservoirs designed by William Errington (1832–1894). It was decided that new reservoirs were needed, so in 1907 Bush designed the first of many reinforced concrete reservoirs with vertical walls and a concrete roof supported by columns. Arch Hill was the first new reservoir built, followed by one at Khyber Pass.

In 1915 the Council instructed Bush to make a comprehensive report on possible water sources for Auckland, including Lake Taupo, the Waikato River and “other sources yielding a substantial quantity and permitting large storage”. This investigation was begun by Arthur Mead (1888–1977), but he volunteered for World War One service so Bush completed the report, which determined that water from the Waitakere Ranges was the most economical source and would satisfy Auckland’s city and growing suburbs for some time to come.

Trench at the construction site of the Upper Nihotupu Dam, 1914-1923, Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries, 1-W1814.

Roads, recreation and other municipal matters

The formation of streets within Auckland City was always a contentious issue requiring large sums of ratepayer’s money. In November 1910 Bush reported on the various types of road metal available and what improvements should be done in each of the city streets. At that time motor vehicles were coming into use causing dust problems on unsealed roads, while many suburban streets were still not properly formed. Bush was able to report on recent international roading conferences where higher standards were being demanded.

The design of the Tepid Baths, opened on 7 December 1912, was probably a collaborative effort between Bush and architect Arthur Sinclair O’Connor. These were originally salt water baths, heated from the Tramways Power Station close by in Hobson Street. Between 2010 and 2012 these baths were significantly upgraded to meet modern safety standards and requirements.

As a result of the Council recognising the value of senior officers being sent overseas, in 1919 Bush went to the United States of America, Canada, and Britain to investigate “various matters of Municipal interest”. Bush reported on how various Councils were elected, the number of councillors and their committees. He also looked into methods for increasing revenue through taxation. Prior to his departure, Bush had reported to the Council on the added financial costs of providing street works, drainage and water supplies to amalgamating boroughs and road boards.

As a respected New Zealand engineer, Bush was elected President of the New Zealand Society of Civil Engineers (now the Institution of Professional Engineers New Zealand, IPENZ), for 1926–27.

After Auckland

Although Bush achieved much during his time in Auckland, his tenure ended with considerable embarrassment. A reinforced concrete wall in his 1912 Mount Eden Reservoir collapsed during the construction of a new neighbouring reservoir just after Bush had resigned in March 1929 to take up his position in Brisbane.

Frederick Furkert (1876–1949), the Public Works Department’s Chief Engineer, investigated the collapse. He found that there had been ongoing leakage at the floor to wall joint, corroding the reinforcing. This leakage was noted a few days before the collapse when Bush, after calculating stresses, asked that the water level be reduced by about eight feet. Waterworks Superintendent G Carr ignored Bush because at the lowered level he thought he could not maintain the supply to consumers.

Furkert’s report was critical of the Council for employing Carr in the role, pointing out that an engineer would have been preferable as they would have understood the design of the structure and maintained it well. Although Bush was ultimately responsible for the actions of his staff, Carr was seen as being at fault. This led to the reorganising of the department and Arthur Mead’s promotion to the position of Waterworks Engineer.

Meanwhile, Bush was now working as the Water and Sewerage Engineer to the Greater Brisbane Council. After his five-year term expired in June 1934, Bush’s appointment was not renewed. In a long letter to the Brisbane Courier Bush outlined the “unjust and undignified” circumstances around his dismissal, which he felt were not merited given the quality of his work for the Council.

During the five years he was Brisbane’s Chief Water Supply and Sewage Engineer there were considerable improvements in both these areas. For instance, a 30 per cent increase in sewerage mains and reticulation mileage was achieved, which saw 27,000 more residents having access to these services.

After his dismissal Bush, then almost 60 years old, became a consulting engineer. While in Australia he also served with the Roads Commission in Queensland and, for a short period before his retirement, with the Commonwealth Works and Services Department. He died in Brisbane on 29 January 1950.

More information

Further reading

Graham W A Bush, ‘Bush, Walter Ernest 1875 - 1950,’ from the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 1 September 2010.