8 Sep 2021

He aha i pai ake ai te hangaroto kaupapa me ngā whakataunga pai ake mo te tangata ma te tuturutanga ō te taumautanga. Why authentic engagement with Māori creates better infrastructure and better outcomes for people.

There was a moment during the almost four-year process to deliver New Plymouth’s stunning new airport terminal, Te Hono, when something shifted in the relationship between local hapū Puketapu and the project team.

“I noticed a change,” says Puketapu creative Rangi Kipa, who became a central figure in the $28.7 million project to rebuild Taranaki’s dated 1960s airport.

“The architectural team, the engineers and all the others we had face-to-face contact with started to see that we were attempting to build something more than four walls and a roof, that this thing we were all contributing to had a soul.”

The deep involvement of Puketapu created a special building, but it has also set a benchmark for Māori engagement in infrastructure projects.

“Traditionally a lot of iwi consultation has been seen as a tick-box exercise,” says Beca’s Matthew Low CMEngNZ CPEng IntPE(NZ), who project-managed the design phase for the terminal and served as engineer’s representative during construction.

“To be fair, this started out that way, too, but as it grew and the design changed, we stepped back and really listened. It was quite a journey.”

Something similar occurred when Watercare Services upgraded its Pukekohe Wastewater Treatment Plant, another project that evolved into a partnership, with mana whenua values and a Māori worldview incorporated into decision-making.

Watercare’s Poutiaki Tikanga Māori (Principal Advisor) Richie Waiwai says it was a challenge for the organisation to appreciate the Māori understanding of the Waikato River as a living being – but it got there. “It’s the kind of authentic engagement we’re moving towards every time there’s a project of that scale and importance. It definitely put a stake in the ground.”

"It’s the kind of authentic engagement we’re moving towards every time there’s a project of that scale and importance."

– Richie Waiwai

Te Hono: exterior

Te Rangapū me te maea

Partnership and visibility

The airport in Taranaki and the plant upgrade on the Waikato, both Engineering New Zealand ENVI Awards finalists, show how engaging closely with iwi on engineering projects can produce better outcomes for everyone involved.

They stand out because arguably they’re the exception – at least for now. Rangi Kipa doesn’t gloss over the strained beginnings of Puketapu’s involvement with the airport project. The land on which the airport stands was acquired through the Public Works Act in the 1960s. It contains a series of pā and urupā (burial sites) along the coastal estate that remain highly significant to the hapū and its identity. Yet when the New Plymouth District Council began planning a more modest expansion of the existing terminal in 2016, Puketapu was told it was one of 20 special interest groups that would have a say.

“We had to remind them, ‘Actually, we are the special interest group here. Without this land being taken off us, you wouldn’t have an airport’,” Rangi says.

Puketapu wasn’t interested in merely being consulted, he adds. “We wanted a partnership – and that’s what we got.”

Waiho i te toipoto, kaua i te toiroa. Let us keep close together, not wide apart.

Rangi’s decades-long career as a sculptural artist, along with his personal journey, made him uniquely qualified to drive the rethinking of the project that followed. Trained as a tauira whakairo (master carver), he’s been commissioned to carve works for universities, government departments and corporates, and helped lead a revitalisation of ta moko.

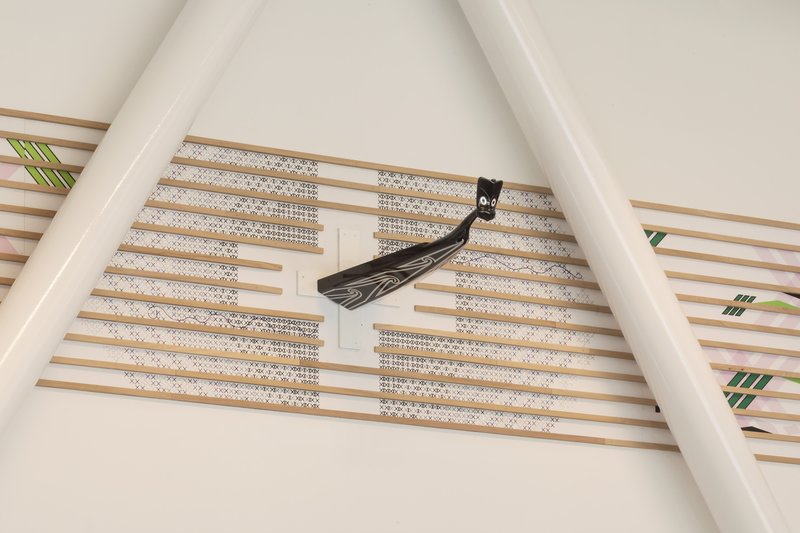

More recently, he started focusing on what he describes as the “invisibility” of Māori in our built infrastructure. On the airport project, he was central to a redesign that embedded the Te Ati Āwa creation narrative of the celestial Tamarau and terrestrial Rongoueroa and their child Awanuiarangi (from whom the iwi descends) in every aspect of the terminal, from its architectural form to the colour scheme to the artwork.

He talks about a process of building trust with the architects and engineers. “I recognise that we were a risk to the project. As soon as you let in a bunch of people who haven’t had the same training and don’t easily fit into the same western qualifications framework, it potentially becomes a problem."

Initially, he did a lot of talking, “trying to backfill their understanding of our experience in Taranaki and what happened here so they could grasp why we wanted to be involved”. “We also spoke aspirationally into the future, tried to push their vision out and make them comfortable with being uncomfortable.”

From Beca’s perspective, it changed the direction entirely, according to Matthew Low. “We listened to the stories and the history, the airport and Beca team presented the functional elements we needed to work through, then we all looked at what could be done. We rewrote the design brief to give a lot more focus on integrating the cultural narrative,” he says, adding that the collaborative relationship with Puketapu on design carried over into construction.

The outcomes? For Beca, its approach to projects involving Māori is now more focused on listening upfront. For Puketapu, Rangi says the collaborative approach has been a healing process. As for the final product, visitors to Taranaki fly into an airport that's architecturally unique and intimately connected to its whenua.

“It makes our people visible again on a landscape where they’ve been made invisible for 140 years,” Rangi says.

It makes our people visible again on a landscape where they’ve been made invisible for 140 years.

– Rangi Kipa

Rangi Kipa

Me hanga kia pai ake, kaua kia nui ake

Building better not bigger

At New Plymouth, a solution was found that balanced cultural considerations with the technical requirements of an airport. It was a similar case with the upgrade of the Pukekohe Wastewater Treatment Plant, a response to population and industrial growth that proposed expanding the plant and relocating the outfall from a neighbouring creek directly into the Waikato River.

Consultation to reconsent the discharge quality began in 2014, followed by nine affected marae coming together as a single entity, Te Taniwha o Waikato, to negotiate and to prepare a Cultural Impact Assessment.

“The challenge for an organisation like Watercare is understanding and appreciating the tribal worldview,” says Richie, explaining that for Māori, an awa (water body) is regarded as a tipuna (ancestor) and a source of identity.

“To have a discharge into the Waikato River and continue to place structures on the bed of the awa would be like cutting a hole in my chest and leaving something in there. That first couple of years the discussions were challenging, because the designs our team put on the table didn’t fit the iwi narrative. The team wasn’t listening to the deeper side of the conversation.”

That understanding evolved with further kōrero about the health of the river. Watercare began to address the wider issues of restoring the Waikato in partnership with Te Taniwha o Waikato, adopting the iwi’s principles that the awa should once again be fishable, swimmable and drinkable.

The project team shifted focus to building better rather than bigger, revising the proposed solution to ensure discharge would not only match, but improve, parameters for flow, bacteria and suspended solids, and water clarity against background levels.

It added cost – the star of the $110 million upgrade is an advanced membrane bioreactor with UV disinfection – but the payoff was a 35-year uncontested consent.

“It wasn’t always a bed of roses, but we worked through an acceptable solution for all, and the awa was the beneficiary,” says Te Taniwha o Waikato Chair, Patience Te Ao.

Her organisation and Watercare have twice-yearly workshops to discuss the scheme’s performance, while the consent’s conditions include regular monitoring.

“It’s an ongoing relationship.”

As for the other partner, Watercare’s Sven Harlos FEngNZ CPEng says: “We broke new ground here.”

Sven says Te Taniwha o Waikato had a clear influence over the water quality parameters and the design.

“The outcome is better for the environment and for everyone in the community along the lower Waikato."

Pukekohe Wastewater Treatment Plant

Ko te arotahi ki ngā kaipūkaha Māori me te Pasifika

Focusing on Māori and Pasifika engineers

The other side of the engaging-with-iwi coin is Māori representation in the engineering profession. Māori and Pasifika make up an estimated one percent of Chartered Professional Engineers in Aotearoa.

One organisation working hard to change that is South Pacific Professional Engineers for Excellence (SPPEEx), whose work focuses on promoting engineering in communities and schools and supporting Māori and Pasifika professionals.

Among various initiatives, SPPEEx, who were finalists at the ENVI Awards, runs engineering career expos in Ōtahuhu that target Māori and Pasifika rangatahi (young people).

In addition, it has established a mentoring programme partnering young engineers with more experienced colleagues and holds networking events throughout the year as a forum to help Māori and Pasifika engineers strengthen and celebrate their distinct identity in the profession.

Success is the increased representation of Maori and Pasifika in the engineering industry with more of them in leadership roles. For SPPEEx, it’s not just about representation but also providing the platform for Maori and Pasifika to network, stay connected and understand their value in the engineering industry, and within their communities.

– Sifa Pole, CMEngNZ (Eng. Technologist) President, SPPEEx

Te Hono: interior

Kō te taumautanga hāngai tonu ki te Māori

Effective engagement with Māori

Hone Hurihanganui is the founding director of Engaging Well, a consultancy that runs “Engaging Effectively with Māori” programmes for organisations in the public and private sector, including Engineering New Zealand /Te Ao Rangahau.

EG: Many engineers will be fearful of making cultural errors. What’s your advice?

HH: Errors are inevitable and you shouldn’t do nothing just because you don’t want to mess it up. The good thing about cultural competence training is that it focuses on the importance of building relationships with people.

EG: What does good engagement look like?

HH: I’d suggest when you’re operating in the homelands of a particular iwi, you should have a relationship already. Tell them who you are and that you’d like to complete any future projects in a way that upholds the iwi’s mana. When the time comes to connect on a particular project, it’s not just transactional – you have an established relationship.

EG: And when engaging on particular projects?

HH: Start early. Find out who the key players are and let them know: ‘These are our plans; we’d like to do this with your blessing and if there are things we need to consider, can we have some guidance on that?’ Engineering firms bring in consultants all the time to advise on special issues and iwi are no different.