20 Sep 2025

New Zealand is not a place where you might necessarily feel comfortable behind the wheel. But as problem solvers and pragmatists, transport engineers are at the heart of work to make our country’s roads safer for all users.

Among OECD countries, New Zealand’s road death rate per 100,000 people in 2022 was the fourth worst, behind Chile, the United States and Colombia. There is a world’s worth of blacktop between us and road safety leaders such as Sweden and the United Kingdom.

But it’s not all bad news. Despite some reversals, the long-run trend is that our roads are becoming safer: the 1990 fatality rate was 21.4 deaths per 100,000 people; in 2022, it was 7.3. Last year, New Zealand recorded its lowest per capita toll since the 1920s (289 fatalities), a result that some have attributed at least in part to the previous government’s speed limit reductions – now being rolled back.

How do we maintain momentum? There’s an argument that driver education – all those billboards and media campaigns – along with stricter enforcement to tackle drink- and drug-impaired driving, and safer vehicles have all helped to reduce deaths, and will continue to do so. But road safety thinking has moved on from “blame the driver” and a relentless focus on education. The current Safe System approach acknowledges that drivers will inevitably make mistakes; the point is to reduce the risk so that they don’t pay for a moment’s bad judgement with their life. It’s about smart highway design and making better use of proven road safety solutions, and transport engineers are at the heart of it.

Working to reduce harm

One thing to get out of the way first: why does New Zealand compare so poorly when it comes to road deaths?

Kaye Clark FEngNZ’s 40-year engineering and management career included various roles with NZ Transport Agency Waka Kotahi (NZTA) including State Highway Manager, Road Safety Programme Manager and Principal Advisor to the agency’s Safety and Environment Group. This year she was presented with Engineering New Zealand’s MacLean Citation, recognising a member who has contributed exceptional and distinguished service to the profession.

“A lot of it is to do with geography,” Kaye says of our relatively high road toll. “New Zealand is an elongated country with a lot of length of roading and much of it is chipseal, and along with the associated infrustructure, it takes a lot to maintain. When you compare it to a place like the UK, which has similar land area but a considerably larger population, we have challenges.”

Statistics make the same point. In 2022, 68 percent of fatal crashes occurred on rural roads. And then there’s the National Road Assessment Programme, or KiwiRAP, which was developed by the AA and the NZTA to assess the safety of our network. In 2010, it rated 90 percent of the state highways using a five-star system. Nearly 40 percent achieved two stars, 56 percent managed three.

Kaye says there is far more in an engineer’s toolkit to improve those roads than when she started her career (“we didn’t even have median barriers”). But there’s also more responsibility under the Safe System approach.

“The engineering now is about trying to reduce conflict areas and trying to reduce the severity if something goes wrong. It’s moved into an ethical space where the system itself is problematic and our duty as engineers is to reduce the harm. What can we do?”

Primarily, road safety is about physics, she says, “… about what the human body can survive”. You can reduce speed limits, of course. But for engineers, the focus is on removing those abovementioned conflict areas. Intersections are a fatality hot spot – so you use roundabouts, which are far more forgiving. Head-on crashes at speed are prevented by median barriers, while fencing and other roadside treatments can save the day if a vehicle leaves the road. Separating cyclists from traffic is another winner.

“There’s better understanding now of the things you can do to improve safety, and they’ve started to standardise these treatments,” says Kaye.

It’s moved into an ethical space where the system itself is problematic and our duty as engineers is to reduce the harm. What can we do?

Western lookout pull-over area of Te Ahu a Turanga: Manawatū Tararua Highway. Photo: NZTA

The newly opened 11.5km replacement for the Manawatū Gorge Highway is a case in point. Known as Te Ahu a Turanga Manawatū Tararua Highway, it features two 100kph lanes in each direction with a flexible median barrier, roundabouts at either end, three rest areas, four lookouts and a shared pedestrian/cyclist path.

Kaye calls it an excellent example of the Safe System approach to road design. Conversely, the Government’s rollback of speed limit restrictions raises the risk of harm. “When you look at our roads, a lot of them aren’t safe at the speed that’s posted,” she says. Regarding the efficiency argument for raising speeds, she says: “The quickest way to bring a road to a stop is having a bad or a fatal crash.”

Whatever happens with speed limits, she adds: “Engineers will work around it and keep doing our best with the tools and the funding we have. We’re problem solvers.”

Modern road safety measures

Engineers are problem solvers, but pragmatists too Aurecon senior civil designer Stuart Hamilton MEngNZ was the roading technical lead on the highway rebuild following the 2016 Kaikōura earthquake, an event that took out 200km of SH1 and around 190km of rail line. Working closely with a NZTA safety engineer, Stuart oversaw the design of the new coastal route, squeezed in beside the railway and between the base of the Kaikōuras and the ocean. It is not a setting in which you can roll out your full bag of road safety tricks. Nevertheless, the team was able to introduce practical solutions, including smoothing corners, installing concrete barriers to prevent rail line ballast falling onto the road, improving drainage and building safe roadside stopping areas.

State Highway 1 rebuild at Irongate Bridge (north of Kaikōura), constructed as part of the North Canterbury Transport Infrastructure Rebuild following the 2016 Kaikōura earthquake. Photo: Aurecon

“It’s hard to quantify, but I believe it is safer,” he says.

Elsewhere, Stuart has been involved in roading projects that capitalised on modern road safety staples. In Marlborough, for instance, he designed a roundabout to replace the hazardous intersection of two high-speed roads, Rapaura Road (wine country’s “Golden Mile”) and SH6.

“Roundabouts reduce your conflict points and make things much easier to define – and there’s only one movement you have to worry about, which is from your right,” he says.

“Median barriers also reduce death and serious injuries. However, they have been also very divisive in terms of the impact to local road users and there has to be a balance found.”

He has also been a safety auditor, which he describes as “effectively doing a peer review” of road design.

“A design team can get lost in the detail and miss the bigger picture. You’re asking things like ‘Have you considered what happens if a car leaves the road here? What about cyclists? What about maintenance? How does that feature fit in?’”

I think about the total experience of the journey, whether that’s in a car, bus or train, or using a bike or simply walking.

His own design work is influenced, subtly but materially, by his other job as a Hato Hone St John ambulance officer.

“I've seen the consequences on the occupants of vehicles that have hit objects – the human body does not cope well with high forces. This has strengthened my approach to ensuring that during design we either remove objects or ensure that they are protected from being hit. Sometimes this means questioning what ‘the book’ says and applying real-world experience to really challenge whether something it the optimum solution.”

Motor vehicle accident exercise run by Hato Hone St John Christchurch Metro Volunteers and Fire and Emergency New Zealand. Photo: Stuart Hamilton

Thinking about all users

It’s a question of mindset. Mott MacDonald New Zealand Managing Director Mike O’Halloran FEngNZ CPEng IntPE(NZ) advises anyone involved in designing or improving a road to think about the vulnerable users. “I think about the children who travel to school on our roading network and what they might encounter along the way. I think about the total experience of the journey, whether that’s in a car, bus or train, or using a bike or simply walking. And I always think of drivers having to negotiate roads at night, especially during bad weather.”

Mike has delivered major transport projects over his 35-year career. The fundamentals still apply – good signage, effective traffic signalling and appropriate lighting all make a difference, he says. And road safety continues to be about more than engineering out risk. “It involves a comprehensive approach, including improved vehicle safety and better driver behaviour.”

That said, he’s also excited about the potential of new solutions. When sitting in an Auckland traffic jam, he sometimes imagines vehicles being guided by sensors along the motorways to regulate traffic flows more evenly.

“There are so many applications and opportunities for Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) to improve our transport networks,” he says, citing recent real-world developments including tidal flow traffic management systems, Vehicle to Everything (V2X) technology, and drones, which may have a role in monitoring traffic patterns and responding to accidents.

“Like any innovation, it’s just a matter of our willingness to embrace and consider.”

Role anything but pedestrian

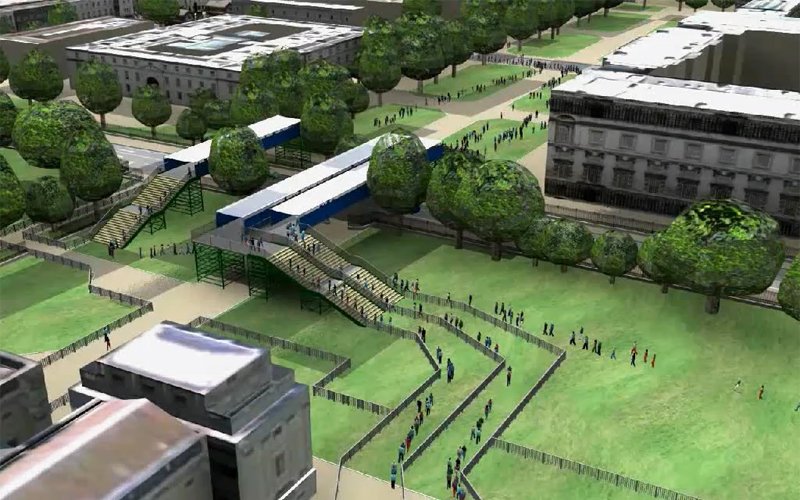

In the buildup to the Rio 2016 Olympic Games in Brazil, Kiwi engineer Martin Peat CMEngNZ CPEng IntPE(NZ) was assigned a very specific task. Ticketholders for events at Deodoro Olympic Park, where the rugby sevens was to be staged, would need to cross the rail corridor and a safer alternative was needed. “The plan was to build a temporary scaffolding bridge,” says the Senior Principal Transportation Planner at Stantec, who won the Engineering New Zealand Young Engineer of the Year Award that same year. “My role was working out how wide the bridge needed to be to get people in and out.”

Modelling pedestrian movements in Greenwich, London, for the 2012 London Olympics. Image: Martin Peat/Alan Kerr

Rio was Martin’s third Olympics, after London in 2012 and the winter games two years later in Sochi, Russia. He specialises in crowd modelling, helping to design temporary infrastructure that ensures enough space to move people safely and efficiently at stadiums and major events. “You’re looking onscreen at people moving through a 3D environment, looking at how they move along footpaths, across intersections and pedestrian crossings, calculating how much space you need for the volume of people likely to turn up,” Martin says. He adds that his job also includes making recommendations about how to queue people and how long queue times are likely to be. “You can’t just let everyone go; it needs to be a managed environment.”

Crowds at the 2016 Rio Olympics, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Photo: Martin Peat

In the 13 years since London, there have been significant changes – notably the advent of rideshare and scooters to get people to and from events. Another trend is the increased targeting of crowds by hostile vehicles. All of it must be fed into the mix, says Martin, who continues to be involved in international events and venue development with Stantec.

And back to that bridge in Rio? How wide? “The answer was 12 metres.”

This article was first published in the September 2025 issue of EG magazine.