17 Oct 2022

Climate change, Covid-19, conflicts and wars (think Ukraine) are leading to diminished food supplies and higher grocery bills. The United Nation warns of a “hurricane of hunger”. Then there are issues around sustainable growth practices and climate change mitigation measures. So, what’s being done here to help find solutions, big and small?

With New Zealand producing enough food for about 40 million people, food security might not affect us directly, but we do have an issue with food equality caused by complex social issues. However, New Zealand still needs to play its part in ensuring a resilient global food supply, says David Hughes, CEO Plant & Food Research.

“Food security is a global concern with multiple drivers. Climate change, for example, will influence where and how we grow food.”

He says: “Having engineers working alongside biologists will help find some of the solutions.”

“We have to build resilience into the supply chain, which can be massively affected by geopolitical issues, natural disasters and pandemics directly affecting our plant and animal food sources.”

Reducing food production’s carbon footprint before 2030 and our net zero carbon goals is another consideration.

“Plants emit less carbon than animals, but there’s room for improvement. We need to work on ensuring efficient tractor use, food chilling and transportation methods, and to consider the fertilisers we use and how we use them.”

David says growing close to consumption is becoming popular in many countries. It can mean creating new growing systems to grow food in controlled indoor environments.

“We already do this with tomatoes, capsicums and strawberries. Leafy greens are being grown in vertical farms. The next evolution will see us growing large perennial trees and vines indoors.”

Plant & Food Research scientists are investigating growing crops in indoor controlled environments. Image: Plant & Food Research

Going greener

A company aiming to create food systems that provide for humanity in partnership with the environment is Christchurch-based Leaft Foods. While looking for ways to reduce food production’s environmental impact, Leaft co-founders John Penno and Maury Leyland Penno FEngNZ developed a way of extracting high-quality, versatile protein from leaves. Called Rubisco, the planet’s most abundant source of protein is found in all green leaves, Maury says.

“But while Rubisco’s trapped inside a plant cell, humans can’t eat – or digest – enough for a sufficient serving of protein. We’re extracting it using a food-safe technology that starts by juicing crops like lucerne and oats. The resultant protein powder has a complete amino acid profile similar to beef.”

Maury lists several benefits: Rubisco is highly digestible, tastes neutral and is soluble (not gritty). It’s versatile and blends into various formulations. It has no known allergens for people.

Furthermore, Rubisco’s potential as an additional food source that won’t sap the environment looks positive. Its carbon footprint is 10 times lower per hectare than conventional dairy protein. Nothing is wasted, either. The leftover silage makes low-emission, low-nitrogen animal feed.

After validating the technology in the lab, Leaft’s next phase is scaling the process to industrial size. Engineering team lead Dr Anne Gordon calls this “a rare design challenge”.

“Every day, our chemical-process engineers work on design optimisation and scale-up using traditional and new processes. Our mission is to develop a design that’s truly sustainable and as energy efficient as possible. It’s a very cool project to be involved with.”

Her team includes biotechnologists and food engineers.

“Their goal is turning the extracted ingredients into great food,” Anne says.

“The raw materials are similar to dairy at a macro level in relation to composition of fats, carbohydrates and protein. But the process doesn’t work in the whey protein isolate process. Nuances in the raw materials present other technical hurdles.”

Maury adds: “We have a long way to go in collecting more data and defining the impact of the Leaft system, but we’re excited about what it could mean for the

future of food.”

Signalling Leaft’s technology’s potential, earlier this year the team raised a US$15 million investment, including Khosla Ventures (early Rocket Lab and LanzaTech backers), Ngāi Tahu Holdings via their New Economy Mandate and ACC’s Climate Change Impact Fund.

Rubisco, a protein powder extracted from crops like lucerne and oats. Image: Leaft

Send in the robots

Several Government-industry funded partnerships are also researching food production practices and opportunities. These include an advanced greenhouse cropping system, pasture health and management, regenerative farming and biodiversity projects.

One such research project is a Southern Fresh Foods’ pilot, testing growing methods for leafy salad vegetables and herbs using an advanced greenhouse cropping system. Announcing the partnership earlier this year, Minister of Agriculture Damien O’Connor said: “We’re looking for consistently high, year-round volumes of quality produce with a lighter impact on the environment."

The technology involves an automated moving gully system that uses robotics to optimise space usage based on the plants’ life stage and size, something the Minister describes as a “climatic-based system and highly technical”. He says the system can achieve substantial yields using significantly less land and reduced environmental impacts from using less water, fertiliser and pesticides.

And as the name suggests, Tauranga-based Robotics Plus also focuses on robotic technologies – autonomous ones – to help address shortages in horticulture and agriculture, and to help create a sustainable and competitive future for the food sector. Founder and CEO of the multi-award-winning company, Steve Saunders, says: “Increasing demand for fresh produce in a labour-constrained market means growers and post-harvest operators need automation, particularly during seasonal labour peaks like spraying, pruning, harvesting and packing.”

He adds: “To reduce reliance on seasonal and migrant labour, we must change how food is harvested, sorted and packed with smart engineering, robotics and automation.”

The Aporo II autonomous robotic fruit packing machine uses AI and neural networks to identify and manipulate fruit during packing. It can pack the equivalent of two to four people, with greater consistency and reliability. It is already used in packhouses here and overseas. The company is also developing and deploying autonomous vehicles to undertake on-orchard and horticultural tasks such as spraying, crop analysis, mowing and trimming.

They’re using their chemical engineering skills to develop innovative food processes that reduce environmental impact from farm to plate.

– Professor Daniel Holland

Supplying the smarts

Given the science securing the food chain from lab to lunch, we’ll need to be smart and resilient.

“The shift in technology will require engineers and plant scientists to create the ideal environment,” says Plant & Food’s David Hughes.

Leaft’s Anne Gordon thinks engineers will cope.

“Our engineering schools and departments actively pursue ways to respond to new technology challenges.”

University of Canterbury Civil and Natural Resources Engineering Professor Daniel Nilsson says sustainability is a theme running through all of the University’s engineering courses.

“Civil engineers are taught to take a whole systems approach to their work. Their role in the food supply chain is to ensure infrastructure – like buildings, water supplies and transport routes – is resilient to changing climate and other environmental hazards.”

Professor Daniel Holland MEngNZ from the University’s Department of Chemical and Process Engineering is also positive. Researchers within his department investigate environmentally sustainable ways to produce food, from plant-based milk alternatives to novel fertiliser technology.

“We’re supplying a regular stream of graduates to join the food industry,” he says.

“They’re using their chemical engineering skills to develop innovative food processes that reduce environmental impact from farm to plate.”

Soil moisture matters

As food security depends on weather and land use, information about climate and land change is critical. Soon a New Zealand/National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) collaboration will start adding high-resolution data to the knowledge bank.

The Rongowai (sensing water) mission involves an advanced Global Navigation Satellite Systems Reflectometry sensor being mounted on an Air New Zealand Q300. It will collect high-resolution, unique samples as the plane flies over the country, says University of Auckland’s project lead, eminent engineer Professor Delwyn Moller.

“We’ll get this rich network of information on soil moisture and inundation over many years and seasons, of a duration relevant on climate scales for climatology. This will help people make choices affecting sustainability and food security.”

She says: “Rongowai will highlight the impact land use is having, which areas are drought-prone, differences between regions, and resiliency towards droughts and floods.”

Once the data has been calibrated and validated it will become publicly available – probably several months after September’s installation.

Image: Lauren Dauphin/NASA Earth Observatory

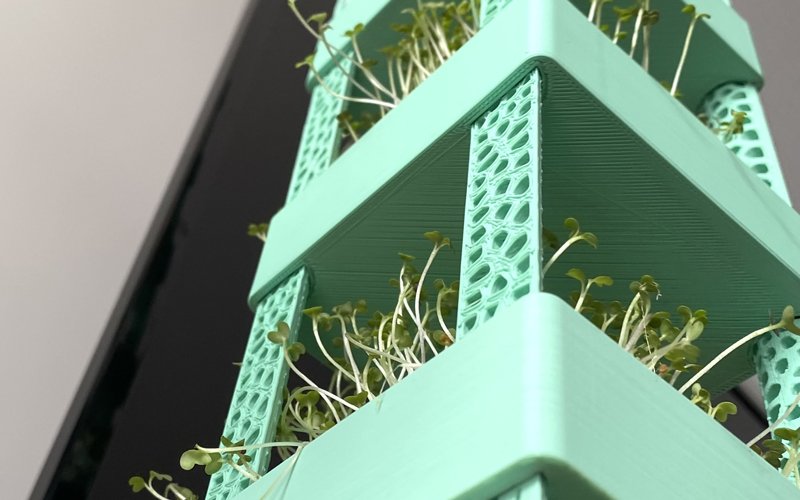

Grow your own – indoor microgreen gardening

Today, people without gardens who don’t like dirty hands but want home-grown food can live their dream. It took a bit of work though. Creating an environmentally-friendly, soilless microgarden that fits on a windowsill saw Thomas Lau MEngNZ of The Foliage Company repurposing disciplines he acquired at engineering school.

He says he treated the project as an engineering challenge, setting his objectives, following project development methodologies, creating CAD drawings, testing and later, undertaking post-production refinement.

The result met all his objectives: a set of attractive, biodegradable, reusable, clean, indoor microgardens, complete with moisture-wicking grow mats, veg and herb seeds.

Image: The Foliage Company