26 Mar 2024

The 2023 Auckland Anniversary weekend floods and Cyclone Gabrielle highlighted the need for a robust land classification system so affected homeowners could gain certainty about the future of their properties. So, just over a year on, how are things working for engineers in Auckland and Hawke's Bay, and what are some of the lessons learnt?

Part of the government’s response to the aftermath of devastation left by the Auckland floods and Cyclone Gabrielle was a new three-category land categorisation system, released in May 2023. Its aim was to create a one-off system to mitigate the worst impacts of those two events, with no explicit intent for it to be used in future events.

Before this land classification system, local and central government did not have a direct role in helping homeowners fix the damage when landslides or flooding occurred. Homeowners were reliant on making an insurance claim. However, the payouts were restrictive and limited by conditions imposed in the Earthquake Commission Act 1993, resulting in some people getting paid much less than expected for land damage.

“The government recognised that this would leave many people trapped by financial constraints in their high-risk, damaged homes,” says geotechnical engineer and Head of Engineering Resilience at Auckland Council, Ross Roberts FEngNZ CMEngNZ (PEngGeol) CPEng.

“We were invited to give our input after the initial idea had been conceived. The Cyclone Recovery Taskforce met with our team of engineers with the shared objective of getting people out of homes where the risk was intolerable.”

Ross’s role since then has been to assess all Auckland properties affected by the landslides using the new categorisation system. That involves interpreting the categories, devising a scheme to implement the categorisation system, then designing a process and engaging people to do the work.

People want a quick answer about their home, so they can move on with their lives

“We’ve created a template approach to doing these assessments in line with the government categories, and made it available on the Auckland Council website, along with some guidance,” he says.

At its core, the system is about understanding risk and identifying which areas are more susceptible to natural disasters. The qualitative descriptions issued by the government have been interpreted by a calculation of annual individual fatality risk and the cost to mitigate the risk to a tolerable level.

“This risk assessment methodology is based on the Australian Geotechnical AGS2007c guidelines. Because this can be consistently and impartially applied, it allows us to be as fair as possible to everyone, including the ratepayers,” says Ross.

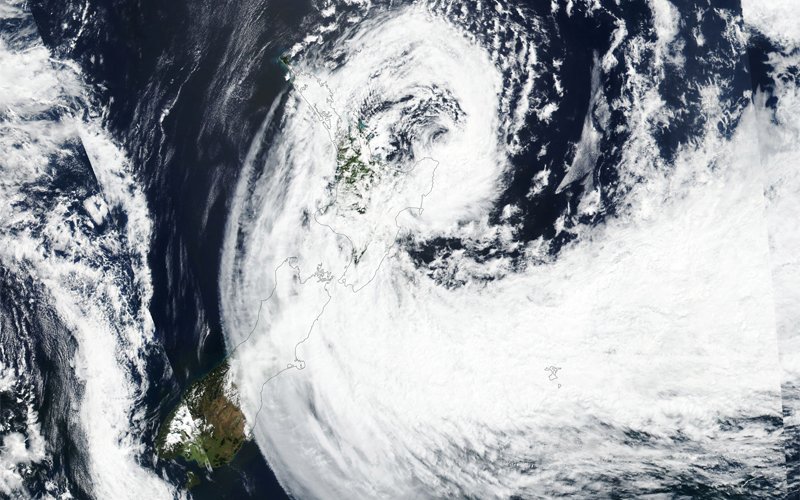

Photo: NASA

In Auckland to date, more than 2,000 affected homeowners have volunteered to be part of the process of classifying their homes and land. With no legislative regime or legal mandates forcing people to move, homeowners can then decide whether to accept the categorisation and the subsequent options for buy-out or funding, where relevant.

“So far, we have completed 512 geotechnical assessments and over 1,000 flood assessments. Of these, 106 are category 3, meaning these homeowners would be eligible for a council buy-out, although we expect the final number to be closer to 500,” says Ross.

He says the system is now robust and working well.

“We have nine companies working with the system, and all the reports they produce look the same, so the information is easy to interpret.”

The balance between speed and robustness appears to be one of the biggest challenges for engineers with the new system.

“People want a quick answer about their home, so they can move on with their lives,” says Ross.

“And we also have to deliver a robust answer that is right for them and their community now and in the future. Those two things are not always very compatible. It’s a tricky line to walk. We have produced a timeline that goes some way to help homeowners navigate the uncertainty.”

Ross and his team are using this natural disaster as an opportunity to collect information about landslides that previously hadn’t been available, and publish it in a national landslide database.

“There are plenty of cases in the past where people have rebuilt in an area at risk, because they weren’t aware of the geotechnical risks of that area.”

Best practices are also shared with other councils in regular meetings to ensure shared learnings. A Rapid Post-Disaster Field Guide is also available online. In addition, instead of the traditional demolition model with the bought-out homes, Auckland Council is using a recycling approach, with as little as possible ending up in landfill.

“It was a model developed for the Eastern Busway in Auckland,” says Ross.

“For instance, kitchen sinks went to local kindergartens to be used in outdoor play areas.”

Good communication helps communities

Your awareness of these issues adds to your credibility both as a technical expert and leader in the community.

In Hawke’s Bay, good communication proved vital as engineers banded together to help communities after Cyclone Gabrielle tore through the area. Structural Principal at Kotahi Engineering Studio in Napier, Aaron Kaijser CMEngNZ CPEng, identified early on the need for a meeting point for the region’s practising engineers, to understand the extent of the situation, share observations and provide updates on best practice and regulatory systems.

“Dave Brunsdon [DistFEngNZ CPEng acting on behalf of Te Ao Rangahau] set up the Hawke’s Bay Engineering Leadership Group (ELG) and tapped me on the shoulder to join and co-chair it with Cam Wylie [CMEngNZ IntPE(NZ)],” says Aaron.

The group facilitated fortnightly forums throughout the year, with the 30–40 attendees joining in-person or online, as presenters from within and outside the region shared experiences and expertise.

The group’s aim was to consider key technical issues involved in the assessment, repair and reconstruction of buildings and infrastructure affected by Cyclone Gabrielle.

“We provided support and best practice [information] to engineering practitioners. The group worked to become an active linkage between engineers, the five local councils involved, central government agencies, the research community and local iwi.”

Communication was initially “frustrating,” says Aaron, in part due to the unknowns in dealing with a flooding disaster and the isolated location of the region. But thanks to the ELG, engineers have been able to upskill on a range of pertinent issues, such as reinstatement of plasterboard, the many provisions within the Building Act (notably Sections 71–74), navigating complex building consent pathways and the insurance process.

“It’s so much about communication,” says Aaron.

“Getting people together on the same page and acting in a true consulting engineer role. The community relies on engineers for answers, and this group has been a terrific conduit to allow this to happen.”

In Hawke’s Bay, terms of reference documents have been produced alongside the land classification system, and the Engineering New Zealand website has been updated to include guidance for engineers making structural and geotechnical assessments after natural disasters.

“My recommendation and learning would be for engineers to upskill in the peripheral areas outside their specific discipline,” says Aaron.

“Your awareness of these issues adds to your credibility both as a technical expert and leader in the community.”

This article was first published in the March 2024 issue of EG magazine.