2 Feb 2026

Ringing the changes in fire safety.

Fire was an ever-present threat to buildings in 19th and early 20th century New Zealand. The majority of buildings were timber and lacked any form of fire safety design or early warning system. The earliest fire alarm was simply a bell installed in the centre of a town, rung manually to alert anyone in earshot.

From the early 1880s, New Zealand cities trialled a system of electric street alarms. When an alarm was activated, it would automatically send a signal to the fire brigade station, ringing a bell there and transmitting a one letter code by telegraph to indicate which city alarm had been activated.

Alarming developments

Some organisations invested in their own fire alarms. One popular system was the invention of Charles May, a mechanical electrician employed by the Dunedin Telegraph Department. He exhibited a model of his Automatic Fire Annunciator in February 1899. The Evening Post gave a detailed description and was full of praise for this “exceedingly ingenious and effective contrivance”.

The alarm consisted of a long metal wire hung close to the ceiling. When the wire became hot, the metal would expand and make contact with an electric magnet and a Morse telegraphic transmitter. The alarm would sound and a disk would drop on an indicator board showing a plan of the building and the location of the activated alarm. If connected to a street alarm system, the fire brigade would be automatically notified.

A successor to Charles May’s Fire Annunciator was the Vigilant fire alarm system. Its inventor was another Dunedin Post and Telegraph Department employee, Matthew Moloney. The alarm also used a metal heat sensor and automatically telegraphed the fire brigade. Insurance companies offered generous rebates for buildings where the alarm was installed. The Vigilant system became well known and was later used all over the world.

Sprinkler systems

Automatic sprinkler systems were another hit with insurance companies. Already popular overseas, they were first used in here in the late 1880s. Auckland businessman Josiah Clifton Firth was among the first in New Zealand to adopt this new technology. In February 1888 he hosted a demonstration of the sprinkler system newly installed in his Quay Street flour mill for the mayor and other local dignitaries and businessmen. The Auckland Star reported with enthusiasm how a pile of wood shavings was set alight and promptly extinguished by the sprinkler. The sprinkler system was connected to the city water supply and was activated by heat. A valve on the sprinkler head was covered by a metal bar held in place with a soft solder. In the heat of a fire, the solder would melt, releasing the sprinkler.

Another early adopter of automatic sprinklers was drapery and soft-goods merchant Sargood, Son, and Ewen. They fitted out their Dunedin warehouse with the Grinnell sprinkler system and May’s Fire Annunciator in 1899 and soon did the same for their Wellington and Christchurch warehouses. Their investment in the sprinkler system had been prompted by the loss of one of their Melbourne warehouses in a fire that swept away an entire block, leaving only a building in which a sprinkler system was installed.

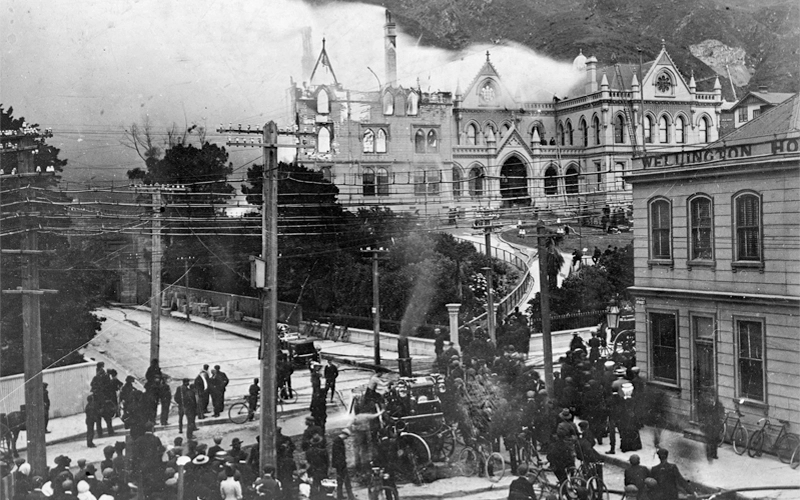

Parliament Buildings fire

1907 fire at Parliament Buildings, Wellington. Photo: Stebbart, G, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. Ref: 1/2-022885-F.

By the early 20th century, automatic alarms and sprinkler systems were established technologies, but not yet widely adopted. It was down to individual business owners whether they chose to make the investment. There was no requirement for public buildings to include fire protection systems. This lack of protection was brought home sharply in this period by the devastating fire at Parliament Buildings in December 1907. Upon discovery, the nightwatchman triggered the manual alarm within the buildings. By dawn the wooden Parliament Buildings were completely destroyed – but the adjoining parliamentary library was saved by its brick walls and metal fire door.

Despite this significant disaster, it was the second half of the 20th century before even limited fire protections were mandated in Aotearoa.

Cindy Jemmett is Heritage Advisor at Te Ao Rangahau.